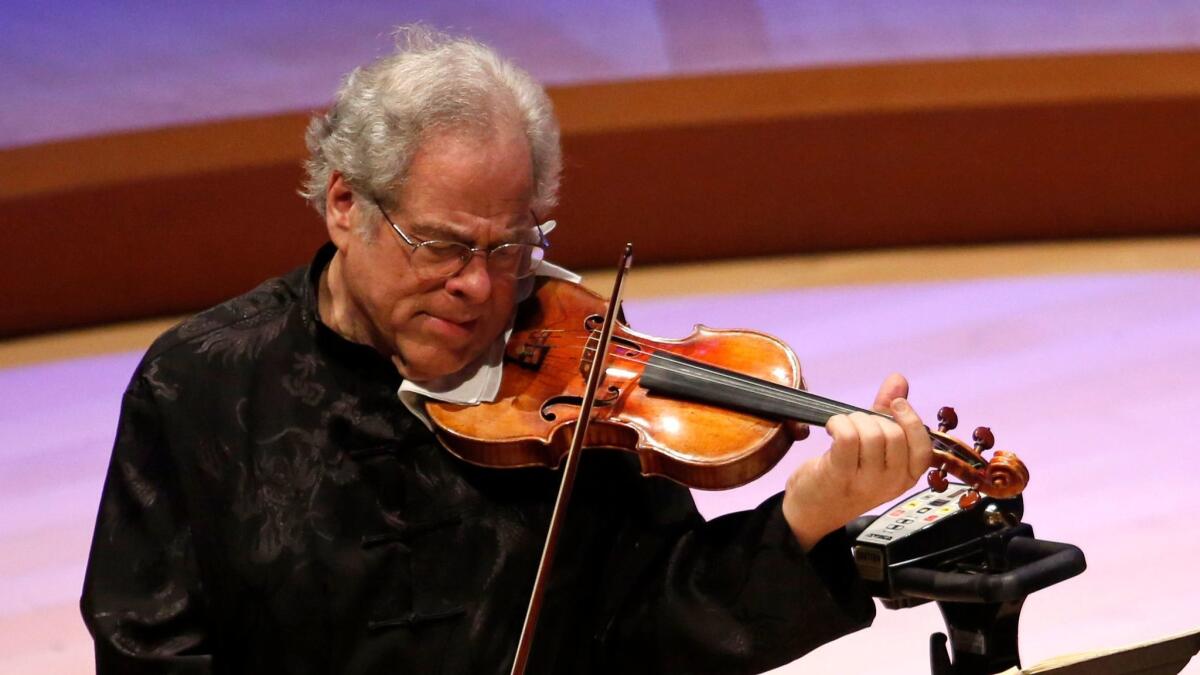

On a night when most stages trade in jump-scares and flashy theatrics, Itzhak Perlman offered something rarer: reverence. His Halloween program, titled “Ghosts of Music Past,” unfolded like a candlelit procession through musical memory — a tribute to the artists who shaped the language of the violin and to the countless unnamed players who kept that language alive.

There were no masks, no billowing capes, no projected cobwebs. Only a chair, a music stand, and the Maestro himself, framed by a circle of votive candles. When he lifted the bow, the hush in the hall felt almost liturgical.

A Requiem Without Words

Perlman opened with a movement from Bach, the Allemande shaped with a tenderness that suggested hands placing flowers on an unmarked grave. Phrases turned inward, cadences resolved like sighs. It wasn’t sorrow for sorrow’s sake; it was gratitude — the kind that makes the chest ache.

From Bach, he traced a lineage: Ysaÿe for the virtuosos who fought their demons onstage; Tchaikovsky for the teachers who coached one more scale after midnight; a Jewish nigun for families who never saw their sons and daughters return from the conservatory, or the front.

Between selections, Perlman spoke sparingly, almost in whispers. He named legends — Menuhin, Oistrakh, Milstein, Stern — and also “the many we never knew, who played in quiet rooms and kept the world gentle for a few more minutes.” The audience answered with silence, the most respectful applause.

Technique as Testimony

What set the night apart wasn’t just repertoire. It was the way craft became confession. Perlman’s tone carried the soft glow of a well-worn violin polished by decades of breath. Shifts were audible, human. Vibrato narrowed in passages of remembrance and bloomed when the line found hope. A few notes arrived with the fragile rasp of time — and somehow that made them truer.

In Sarabande, the bow barely touched the string; you could hear the hall listening. In Tzigane, he let the gypsy fire flicker without spectacle, a portrait of joy remembered through tears. If Halloween’s myths belong to ghosts and shadows, Perlman gave us the gentler ghosts — teachers correcting posture, mothers humming through closed doors, orchestras tuning in cities that no longer exist.

Candles for the Unnamed

Midway through the program, house lights dimmed further. Ushers placed small LED candles along the aisles. A screen behind the stage displayed a rolling list of names: not just the titans, but local choir directors, public-school string teachers, orchestral section players who retired without headlines. People in the audience gasped softly as familiar names appeared; a few raised their candles, both hands trembling.

Perlman then introduced a brief “moment of listening.” No playing, no speaking — just sixty seconds of shared stillness. It felt like a cathedral built of breath.

The Piece That Broke the Room

The emotional summit arrived with Ernest Bloch’s “Nigun.” Perlman’s opening note hummed like a yahrzeit candle catching flame. Melismas bent toward an ache that never quite resolved, and when the theme returned — older, wiser — you could sense the hall exhaling. A woman near the front pressed a program to her lips. A teenager in the balcony wiped his eyes with a sleeve. The stage lights warmed from winter-white to gold.

It wasn’t grief that broke the room. It was recognition: of the lives that built our present, of the songs that carried us here.

A Benediction for the Living

For his encore, Perlman chose the simplest thing — a lullaby. No announcement. He just played it, tender as a grandfather’s hand on a fevered brow. Notes fell like slow rain on dry earth. When he finished, he let the bow hover, as if asking the silence for permission to end.

He spoke once more. “For those we’ve lost,” he said, “and for those who keep playing.” Then he smiled — that small, conspiratorial Perlman smile that says music is still the best trouble to get into — and set the bow down.

The ovation rose carefully, like a congregation standing. People didn’t cheer at first; they breathed. Then the roar came, layered and bright, and yet even that felt less like applause than affirmation.

Why It Mattered

In an age of noise, “Ghosts of Music Past” reminded us that memory is an instrument too — one we tune with gratitude. Halloween so often glorifies fear. Perlman’s tribute honored courage: the courage to practice, to teach, to show up with a violin and insist that beauty still belongs to us.

When the house lights finally returned, the candles kept glowing — tiny anchors against the tide. Outside, the night was cold and ordinary. Inside, something had shifted. We hadn’t been spooked. We’d been steadied.

And somewhere, in the long hallway of music’s afterlife, the ghosts were smiling — not because we mourned them, but because we remembered to listen.